Four letters between writer and Trappist monk Thomas Merton and college professor Rosemary Radford Ruether are presented. The correspondence was begun by Ruether in 1966 and lasted for 18 months. The letters deal primarily with the issue of monastic renewal.

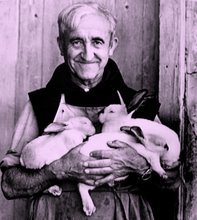

IN 1966 Rosemary Radford Ruether initiated a correspondence with Thomas Merton, the widely published spiritual writer and Trappist monk. Radford was 29 and teaching at Howard University in Washington, D. C. She recalls that she was looking for "a genuine Catholic intellectual peer- with whom she could be ruthlessly honest about my own questions of intellectual and existential integrity." The correspondence, which lasted 18 months, is especially revealing of some of Metton's reflections on--and struggles with--the monastic life. The complete text of the correspondence, At Home in the World, edited by Mary Tardiff, O.P, will be published next month by Orbis Books.

Excerpt

March 9,1967

DEAR ROSEMARY:

Thanks for the new letter, received this morning. I can type now, for a while, and will try to get enough down on paper to serve as a reply that will forward the discussion. Shock? No, not that. But just a sort of dismay because I felt that your last letter--perhaps written hastily--was not in tune with what you had been saying, and after reading the article on "Community and Ministry" (which I liked very much), I felt that the letter was not in tune with this either. The impression I got from the letter, the one with "Community and Ministry," which you thought shocked me, was that you were putting monks on an entirely different basis from the rest of the church, and saying that our charism-vs.-institution struggle was radically different from anybody else's, because the basis on which we stood was theologically impossible and, in fact, heretical, pagan, diabolical. Next thing, I thought, I'll be burnt at the stake by radical Christians. Once you admit that we are all pretty much in the same pickle, and that we face varying forms of the same struggle, I breathe easier.

In a word, what we all need is the simple elementary "freedom to begin where we are" and to really rethink in a radical and creative way our place in the church--and adapt institutional structures, as far as possible, to serve this creative understanding. But honestly, your view of monasticism is, to me, so abstract and so, in a way, arbitrary (though plenty of basis in texts can be found) that it is simply poles apart from the existential, concrete, human dimension which the problem has for us here. The thing that dismays me is the problem of groping around for a place to start talking about it all. Perhaps the best thing would be to start from my own personal motives. Let me put it this way: I am so far from being "an ascetic" that I am in many ways an anti-ascetic humanist, and one of the things in monasticism that has always meant most to me is that monastic life is in closer contact with God's good creation and is in many ways simpler, saner and more human than life in the supposedly comfortable, pleasurable world. One of the things I love about my life and, therefore, one of the reasons why I would not change it for anything is the fact that I live in the woods and according to a tempo of sun and moon and season in which it is naturally easy and possible to walk in God's light, so to speak, in and through his creation. That is why the narcissist bit in prayer and contemplation is no problem out here, because, in fact, I seldom have to fuss with any such thing as "recollecting myself" and all that rot. All you do is breathe and look around and wash dishes, type, etc. Or just listen to the birds.

I say this in all frankness, realizing that I can be condemned for having it so much better than almost anybody. That is what I feel guilty about, I suppose, but certainly not that I have repudiated God's good creation. Sure, it is there in the cities too, but in such a strained, unnatural, tense shape. I won't go into that angle of it. But, in point of fact, when I buy your "academic" argument for monasticism it is partly because I want to share this lovely life with all my friends, and I would be willing to have monks run national parks or something if it would help us do so. Absolutely the last thing in my own mind is the idea that the monk de-creates all that God has made. On the contrary, monks are and I am, in my own mind, the remnant of desperate conservationists. You ought to know what hundreds of pine saplings I have planted, myself and with the novices, only to see them bulldozed by some ass a year later. In a word, to my mind the monk is one of those who not only saves the world in the theological sense, but saves it literally, protecting it against the destructiveness of the rampaging city of greed, war, etc. And this loving care for natural creatures becomes, in some sense, a warrant of his theological mission and ministry as a man of contemplation. I refuse in practice to accept any theory or method of contemplation that simply divides soul against body, interior against exterior, and then tries to transcend itself by pushing creatures out into the dark.

What dark? As soon as the split is made the dark is abysmal in everything, and the only way to get back into the light is to be once again a normal human being who likes to smell the flowers and look at girls, if they are around, and who likes the clouds, etc. On the other hand, the real purpose of asceticism is not cutting off one's relation to created things and other people, but normalizing and healing it. The contemplative life, in my way of thinking (with Greek Fathers, etc. , is simply the restoration of man, in Christ, to the state in which he was originally intended to live. Of course, this presents problems, but I am in the line of the paradise tradition in monastic thought, which is also part and parcel of the desert tradition and is also eschatological, because the monk here and now is supposed to be living the life of the new creation in which the right relation to all the rest of God's creatures is fully restored. Hence, desert father stories about tame lions and all that jazz.

You will say this is not theology.

Well, let's look a little at the literature. Though it is easier to find statements that seem to be and, in fact, are radically negative about material creation, I would say one must not oversimply. This business of saying, as you do, that the monk is in the same boat with the Manichean but just refuses, out of a Christian instinct and good sense, to be logical about it, is, I think, wrong. About early monastic literature, two things have to be observed first of all:

1. There are several different traditional blocs of texts. The Syrian tend to be very negative, gnostic, Manichean (exception made for Ephrem, who is utterly different). But note, for instance, the development in the ideas of Chrysostom. Then there is the reaction of Basil and the Cappadocians (blending Syrian with Egyptian-Greek lines). The Greek-Egyptian hermit school. Origenist and Evagrian, less negative than the Syrians, more balanced. Here in the Life of Anthony, a classic source if there ever was one, Athanasius goes to great pains to have Anthony say that all creation is very good and nothing is to be rejected; even the devils are good in so far as they are creatures, etc., etc. The Coptic school, especially in the Pachomian text, the most biblical of the bunch, quite Old Testament, in fact, and with an Old Testament respect for creation and God's blessing upon the creatures.

2. In the literature itself there are questions of literary form and other such matters that are very important. Stories are told and statements are made that push one idea to an extreme. The balance is restored in other stories that push the opposite idea to its extreme. Thus there are stories that prove that no one can possibly be saved unless he is a monk, and other stories in which the greatest monastic saints are told in a vision to go down town and visit some unlikely looking layperson (married and all) who turns out to be a greater saint than he by just living an ordinary life. A restudy and rethinking of these sources will, I am sure, show that you are much too sweeping when you say that monasticism is simply a repudiation of the world in the sense of God's good creation. On the contrary, it is a repudiation--more often--of the world in the sense of a decadent, imperial society in which the church has become acclimatized to an atmosphere that is basically idolatrous. Now, all right, the history of monasticism does show that the monks themselves got "demonized" by being incorporated into the power structure and all that. This I have said myself, and I agree with you. But also the reactions are much more important than you seem to realize. For instance, the very significant lay-hermit movement in the 11th century, lay solitaries who were also itinerant preachers to the poor and the outcasts who had no one to preach to them (since there was no preaching in the parishes and even in many cathedrals). These were forerunners not only of Franciscanism but also of Protestantism and pre-Protestant sects like the Waldensians, etc. You have probably run into some of this, but not connected it with the hermits.

Once this more existential view of the whole monastic situation becomes possible, then I think it is possible to agree with you that monasticism has "lost its soul" in so far as it has become committed to an iron-bound institutionalism built on a perverse doctrine of authority-humility-obedience. The bind here is worse than anywhere else in the church, insofar as the emphasis on perfect obedience as "the" monastic virtue (which of course it is not) puts the monk bound hand and foot in the power of his "prelate" (now no longer charismatic and chosen spiritual father but his boss and feudal lord and maybe general in chief). Then when renunciation of the world is fitted into this context by being a prohibition of any sight or sound of anything outside the monastic walls, any concern with any human activity outside the walls, and so on, plus a Jansensistic repudiation of all pleasure, then you do get a real monastic hell: I don't deny that at all, I have lived in one. But again, the answer is to start with saving the poor blighters who are caught in such a mess and to save the beautiful life that has been turned into a hell for them when it should be what it was first intended to be. The terms in which I have been stating this have been deliberately "humanistic" in order to emphasize the fact that we are not simply refusing to have anything to do with God's good creation, and that the idea of "salvation from the world instead of salvation of the world" makes a nice slogan, but it does not really apply at all to our case properly understood, only to the distortion. I agree, of course, that the distortion has been terribly widespread, and is. From here on out, we can get at the really important idea of eschatological alienation. Another time. And also a further development of the idea of the relation of the monk to the rest of the church. In passing, I admit that I myself see a serious problem in the idea of a monastic church constituted outside of, and over against, a church in the world. We'll have to go into that too. More in tune with this letter: an example of what I myself am doing in my "secularized" existence as a hermit. I am not only leading a more "worldly" life (me and the rabbits) but am subtly infecting the monastery with worldly ideas. I still am requested to give one talk a week in community, and have covered things like Marxism and the idea of dialogue a la Garaudy, Hromadka and so on, and especially all kinds of literary material, Rilke for some time and, now for a long time, a series of lectures on Faulkner and his theological import. This is precisely what I think a hermit ought to do for the community which has seen fit deliberately and consciously to afford him liberty. I have a liberty which can fruitfully serve my brothers, and by extension I think it indicates what might be the monk's role for the rest of the church. Not only literature, of course; all sorts of things. I think too that being in a position to grab on to some Zen I have an obligation to do this, though Zen is not something one has. It is more a way of being (it is least of all a religious doctrine or ideology). More about that some other time. Sorry this was so long, but I hope I have been able to make clear that the only world I am trying to get saved from is that of the principalities and powers, who may or may not have computers and jet planes at their disposal; that too is another question. The rest of it, I am with you in wanting to save and in wanting to have the freedom to work for effectively. I am returning the manuscript of your article, which is very good indeed. I agree perfectly.

With all my best wishes, and without shock,

Yours, Tom

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment